Nairobi, Kenya – Global health experts have embarked on a Sh1.2 billion research project aimed at understanding the spread and impact of Rift Valley fever (RVF), a mosquito-borne viral disease that continues to threaten human health, livestock, and food security across Africa.

The collaborative effort brings together researchers from Washington State University–Global Health in Kenya and the Kilimanjaro Clinical Research Institute in Tanzania, alongside a network of international partners. The study is expected to generate data that will guide vaccine development and outbreak preparedness for the disease, which remains a priority concern for the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI).

A Neglected but Deadly Threat

Rift Valley fever was first identified in Kenya’s Rift Valley in 1930 and has since spread to other African countries and parts of the Middle East. The disease affects livestock such as cattle, sheep, goats, and camels, and humans can contract it through mosquito bites or direct contact with infected animals.

Although most human cases are mild, the disease can cause severe haemorrhagic fever, encephalitis, or vision loss, with fatality rates in serious outbreaks reaching as high as 50 per cent in hospitalised patients. Outbreaks are often linked to periods of heavy rainfall and flooding, conditions that fuel mosquito breeding and viral transmission.

Despite its impact, there is still no licensed vaccine for human use. Vaccines for livestock exist, but they are limited in scope and accessibility. CEPI has listed RVF as a priority disease because of its epidemic potential and the significant gaps in prevention and control.

“Rift Valley fever has been neglected for far too long,” said Dr Kent Kester, Executive Director of Vaccine Research and Development at CEPI. “This research will tell us whether large-scale vaccine trials are feasible, where they should be conducted, and how long they might take. If cases are too infrequent for a traditional trial, we will need to explore alternative regulatory pathways to bring a human vaccine to market.”

Vaccine Development Underway

Alongside this Sh1.2 billion research push, vaccine development is advancing on several fronts. Oxford University and the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme are preparing to test the ChAdOx1 RVF vaccine in a Phase II trial involving 240 Kenyan volunteers. This candidate vaccine uses the same platform as the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine and has already shown promising safety results in earlier studies.

In South Africa, Afrigen Biologics is developing the first mRNA-based vaccine for RVF, with nearly $6 million in CEPI support. The vaccine is expected to move into Phase I clinical trials in the coming years and could strengthen Africa’s vaccine production capacity. Meanwhile, UC Davis in the United States has secured $28 million to lead multi-country vaccine trials under a One Health framework that integrates both human and veterinary research.

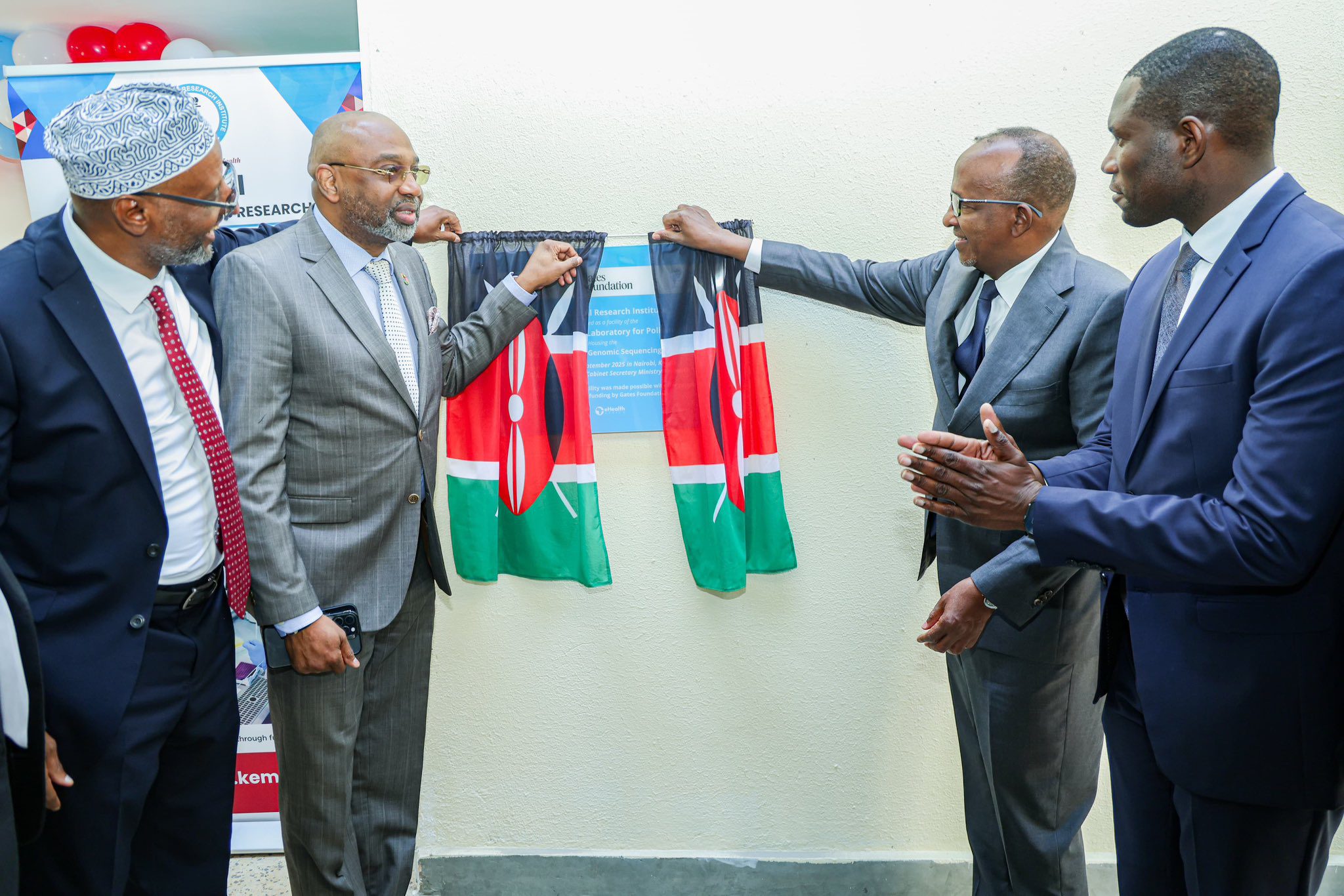

Genomic Surveillance and Forecasting

Scientists are also building tools to monitor and predict outbreaks. The International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) in Nairobi has introduced genomic technologies that allow faster and cheaper sequencing of RVF strains, making real-time surveillance more accessible. Computational tools for tracing viral lineages have also been developed, helping to identify whether new outbreaks stem from local strains or cross-border transmission.

In addition, predictive modelling tools are being refined to combine climate, environmental, and epidemiological data to forecast outbreak risks. Such systems are particularly important as climate change alters rainfall patterns and increases the likelihood of flooding, which creates ideal conditions for mosquito proliferation.

Why the Project Matters

The new Sh1.2 billion research initiative will forecast the number and likely location of human RVF infections across Africa. This information is critical for vaccine developers and policymakers because large-scale vaccine trials can only be conducted where the virus is actively circulating.

“Knowing where cases are likely to occur allows us to better estimate vaccine demand and prepare for eventual rollout,” CEPI noted in its August 21 update.

For Africa’s pastoralist communities, the research holds even greater significance. RVF outbreaks not only cause illness and death in people and livestock but also disrupt trade, reduce food production, and damage livelihoods. By advancing vaccines, surveillance tools, and predictive models, scientists hope to move from crisis response to proactive prevention.

If successful, this collaborative project could not only lead to the first licensed human vaccine against Rift Valley fever but also provide Africa with a stronger blueprint for managing future zoonotic disease threats.

Leave a Reply